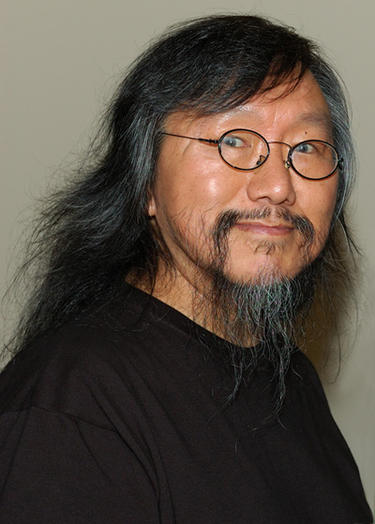

Alootook Ipellie (1951-2007)

Alootook Ipellie was an Inuit translator, illustrator, reporter and writer. Primarily known for his poems, short stories and many illustrations—which vary from political cartoons and comic strips to portraits and larger drawings—Ipellie has been featured in several magazines, journals and anthologies. Though much of his work is still hidden away in private collections and books, he has an important place in Inuit and Canadian literary traditions. Described as a prodigious artist and a man of few words who spoke volumes through his essays, stories and poetry (Amagoalik 42), Ipellie explored and gave voice to many of the cultural, social, political and economic issues affecting Indigenous communities in Northern Canada.

Ipellie was born in 1951 in Nuvuqquq, in the Qikiqtaaluk region on Baffin Island in what is now Nunavut. His father died shortly after his birth; as result, his family experienced considerable hardship when he was young. When Ipellie was four, his mother and stepfather moved the family to Iqaluit (formerly Frobisher Bay), to live in a township the federal government had set up in order to create permanent Inuit settlements in the North and help contain introduced diseases.[1] At age five, however, Ipellie was diagnosed with tuberculosis, separated from his family and sent to Mountain Sanatorium in Hamilton, where he had to learn English in order to communicate. So began a pattern of moves between the North and South that, as one scholar has pointed out, in many ways characterized the rest of Ipellie’s life.[2]

Ipellie continued to live with his mother and stepfather in Iqaluit until he was ten. Due to his stepfather’s struggles with alcoholism—a problem that has historically plagued the Arctic to a much greater degree than other regions in Canada—Ipellie decided to leave home and live with his uncle.[3] He later moved in with his grandparents, who regularly took in and adopted other children from the community who weren’t receiving the care they needed at home.[4] During this time, Ipellie grew close to his uncle, who maintained a more traditional Inuit lifestyle and who, according to Ipellie, was responsible for teaching him about his people’s connection to the land. He was also greatly influenced by his grandfather, Inutsiaq,[5] a well-known carver, who instilled in him a fascination with storytelling.[6]

Thanks to the lack of a secondary schooling system in the North, however, Ipellie was forced to leave home and enroll in a school in Ottawa in 1967, where he was billeted with an English-speaking Canadian household. He struggled greatly with the educational format, the distance from his family, and an overwhelming sense of culture shock—one that caused him to question whether he was still “an Innumarik, a real Inuk” (Ipellie, “Introduction” vii).[7] In the years that followed, Ipellie was torn between attempting to pursue his interest in art, find a reliable means of employment and return home to Iqaluit, while also grappling with his school counsellor’s firm opposition to his dream of going to art school and his repeated relocation to different cities, often against his will.

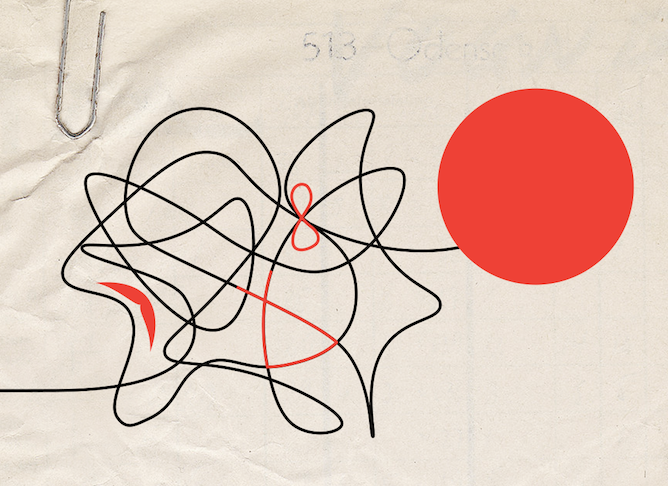

Ipellie eventually made his way home but, shortly after his return, found himself unemployed and battling depression. After a three-month stint working for CBC Radio as an announcer and producer, Ipellie became involved with the Inuit Tapirisat (now Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, or ITK), an organization whose aims were to draw attention to Inuit community issues and to preserve and promote Inuit culture. He moved to Ottawa in 1972, and during the early 1970s, sold his first pen-and-ink drawings and published some of his early poems and stories in North/Nord and Inuktitut. In 1973, he started work as a translator for the magazine, Inuit Monthly (now renamed Inuit Today). At first he produced the occasional drawing on commission, but by 1974, in order to fill empty space in the magazine, he had begun a regular cartoon strip, dubbed “Ice Box,” which examined, with humour, irony, patience and wit, the ways in which southern Canadian culture had influenced and changed Indigenous communities in the North.[8]

Throughout the remaining 1970s, Ipellie’s roles and responsibilities with Inuit Monthly expanded: he began to contribute poems and photographs; managed the magazine’s design; wrote a regular column, “Those Were the Days”; and was the magazine’s primary editor from 1979 to 1983. During this period, he also found time to collaborate with Robin Gedalof (later Robin McGrath) on an anthology of Inuit writing, Paper Stays Put (1980), where several of his stories, poems, and images were featured. In the 1980s and early 1990s, he contributed to and worked as an editor for many different magazines and journals, including Inuit (1984-1986), a magazine published by the Inuit Circumpolar Conference; Nunavut Newsletter (1991-1993), which was published by the Tugavik Federation of Nunavut, the organization responsible for the creation of the Nunavut territory; and Nunatsiaq News, a weekly newspaper distributed in Nunavut.

Ipellie published his first collection of short stories and drawings in Arctic Dreams and Nightmares in 1993. According to some scholars, Arctic Dreams marks a turning point in Ipellie’s work and reputation as an artist; his stories, poems, and drawings, which had previously been created for a largely Inuit audience, now captured the attention of Southern critics and garnered him well-deserved, if somewhat belated, recognition in academic and critical spheres across the rest of Canada (Kennedy, “Southern Exposure” 356-358). As one of the first single-authored short story collections by an Inuit artist, Arctic Dreams became popular in undergraduate Indigenous literature courses in Canada, and remained in print until 2006.[9]

Ipellie’s work has since been featured in numerous magazines and journals as well as anthologies including Penny Petrone’s Northern Voices: Inuit Writing in English (1988); various editions of Moses and Goldie’s Anthology of Canadian Native Literature in English (1992, 1998, 2005); The Exile Book of Native Canadian Fiction and Drama (2010); Gillian Robinson’s The Journals of Knud Rasmussen: A Sense of Memory and High-Definition Inuit Storytelling (2008); and Sophie McCall et al.’s Read, Listen, Tell (2017). He worked with Gedalof on what was intended to be an Inuktitut language textbook for use in Northern Schools, which was never published/completed; with Hartmut Lutz on The Diary of Abraham Ulrikab (2005); with David MacDonald on a non-fiction children’s book, The Inuit Thought Of It: Amazing Arctic Innovations (2007); and with Anne-Marie Bourgeois on I Shall Wait and Wait (2009). He also wrote a novel, titled Akavik, The Manchurian David Bowie, which has yet to be published.

Despite his profound ability to capture the complexity of what it means to be Inuit today, much of Ipellie’s work still has not received the attention it merits, likely because it does not conform to contemporary expectations of what Inuit art should look like.[10] Recent exhibitions, such as the internationally touring retrospective, “Walking Both Sides of an Invisible Border” (2018), which showcased over 100 pieces of his work from the 1970s until his death in 2007, are seeking to revise his reputation as an Inuit artist and draw attention to his lasting voice and vision.

Selected Readings:

Ipellie, Alootook. Arctic Dreams and Nightmares. Theytus Books, 1993.

———. The Inuit Thought of It: Amazing Arctic Innovations. With David MacDonald. Annick Press, 2007.

———. “My Story.” North/Nord. vol. 30, no. 1, 1983, pp. 54-58.

———.“Those Were the Days.” Inuit Monthly (later Inuit Today), 1974-1976.

Ipellie, Alootook and Anne-Marie Bourgeois. I Shall Wait and Wait. Ed. Glen Downy. Rubicon Publishing, 2009.

Ipellie, Alootook and Robin Gedalof. Paper Stays Put: A Collection of Inuit Writing. Hurtig, 1980.

Works Cited:

Amagoalik, John. “Alootook Ipellie.” Inuktitut, issue 104, Winter 2008. pp. 40-45.

Bennett, John, and Susan Rowley. Uqalurait: An Oral History of Nunavut, MQUP, 2004.

Kennedy, Michael P.J. “Alootook Ipellie: The Voice of an Inuk Artist: Interview by Michael Kennedy.” Studies in Canadian Literature, vol. 21, no. 2, 1996. pp. 155-164.

———. “Border under Siege: An Author’s Attempt to Reconcile two Cultures.” INUSSUK: Arctic Research Journal 2, 2002. pp. 75-98.

———. “Southern Exposure: Belated Recognition of a Significant Inuk Writer-Artist.” The Canadian Journal of Native Studies, vol. 15, no. 2, 1995. pp. 347-361.

McMahon, Kimberley. “Dreaming an Identity between Two Cultures: The Works of Alootook Ipellie.” Kunapipi, vol. 28, no.1, 2006. pp. 108-125.

———. Indigenous Diasporic Literature: Representations of the Shaman in the works of Sam Watson and Alootook Ipellie. U of Wollongong, PhD dissertation, 2009.

Ipellie, Alootook. “Introduction.” Arctic Dreams and Nightmares. Theytus Books, 1993. pp. vi-xx.

———. “Those Were the Days VII.” Inuit Monthly. vol. 3, no. 9, 1974. pp. 82-84.

———. “Those Were the Days IX.” Inuit Today, vol. 4, no. 4, 1975, pp. 70-73.

———. “Those Were the Days XII.” Inuit Today, vol. 4, no.7, 1975, pp. 66-69.

———. “Those Were the Days XIV.” Inuit Today, vol. 4, no. 10, 1975, pp. 46-49.

Additional Resources

For an analysis of Alootook Ipellie’s aesthetic sense of space, see:

Desrochers-Turgeon, Émélie. "Between Lines and Beyond Boundaries: Alootook Ipellie’s

Entanglements of Space." Études Inuit Studies, vol. 44, no. 1-2, 2020, pp. 53–84. https://doi.org/10.7202/1081798ar

Abstract

Manifold representations of the dwelling are expressed in the work of artist, poet, writer, editor, and activist Alootook Ipellie in the bi-monthly publication Inuit Today in the 1970s and 1980s, as a cross-section through key moments in Inuit Nunangat history. This essay thus examines Ipellie’s representations of space—not as an attempt to theorize Inuit space but rather to offer reflections on how these representations challenged ways of knowing and interpreting Arctic communities. We first address the Arctic representation in Ipellie’s work, which emphasizes the existing richness of the land according to Inuit perspectives as opposed to Qallunaat (non-Inuit) interpretations. His drawings also offer political comments on land disputes and the exploitation of territory. We then explore the representation of buildings, as Ipellie witnessed the transition from traditional to government housing. Ipellie’s humour-based approach constituted a strong social and political critique of housing issues and settler-colonial building practices. This artist acknowledged Inuit ingenuity when speaking of traditional housing, thus advocating for Inuit knowledge, invention, and built heritage. Lastly, we discuss the representation of multiple voices in the struggles over space, including Inuit communities and non-human agents, such as animals and land. Dwelling on the notion of “lines” and “the in-between”, we consider the thickness of Ipellie’s drawn lines and attend to the multiple entanglements between the artist’s political cartoons and the many lines of settler-colonialism, such as boundaries, frontiers, roads, pipelines, spatial construction, buildings, and planning.

For a discussion of the impact Inuit Art has had on the global stage, see,

Duchemin-Pelletier, Florence. “Taking The Floor.” Edited by Peter J. Schneemann and Thierry Dufrêne. CIHA Journal of Art History, vol. 1, 2021, pp. 53–67, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.57936/terms.2022.1.92650.

Abstract

The inherent dynamics and challenges of speaking up vary from one context to another. Depending on both cultural expectations and socio-political history, local voices have sometimes remained unheard on the global stage. Drawing on the example of the Canadian Inuit, this paper considers the strategies undertaken by artists and activists when it comes to “taking the floor.” It first focuses on the genealogies of struggle, both internal and transcultural, before examining the question of multivocalities. Finally, it addresses the role of local epistemes and suggests shifting perspectives so they can be part of a global art history.

For a discussion of the relationship between Indigenous and settlers when translating Indigenous texts, see:

Henitiuk, Valerie, and Marc-Antoine Mahieu. “‘who will write for the Inuit?’” Tusaaji: A Translation Review, vol. 8, no.1, 3 June 2022, https://doi.org/10.25071/1925-5624.40422.

Abstract

This article examines the circumstances surrounding the first publication of an Indigenous novel in Canada, namely Uumajursiutik unaatuinnamut by Markoosie Patsauq, in 1969-70 It describes the context of the federal government’s cultural policy, in particular within the then Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, and how this impacted relations with Inuit generally speaking, but also how it set the stage for bureaucratic involvement in the production of an English adaptation of Patsauq’s text, widely known today as Harpoon of the Hunter. Finally, we present our own rigorous new translations, titled Hunter with Harpoon/Chasseur au harpon, done in collaboration with the author and based on his original Inuktitut manuscript, suggesting some more ethical practices for working with Indigenous source texts.

For a discussion of emerging Indigenous performance in modern colonial art contexts, specifically through the work of Tanya Tagaq, see

Gagnon, Olivia Michiko. “Singing with Nanook of the North: On Tanya Tagaq, feeling entangled, and colonial archives of Indigeneity.” ASAP/Journal, vol. 5, no.1, 2020, pp. 45–78, https://doi.org/10.1353/asa.2020.0002.

Allootook Ipellie is cited:

“[Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit]… offers one important way of listening to Tagaq’s solo practice: as the enactment of Inuit culture as an embodied practice of adaptability, one whose insistence on the now of tradition evidences an urgent responsiveness to changing conditions. In “The Colonization of the Arctic,” the late Inuk artist and writer Alootook Ipellie notes that:

For the original inhabitants of this at once terrible and beautiful land, the last 500 years have been full of surprises. For thousands of years, it seemed their lifestyle would never change. But their contact with human beings from other lands and other cultures forever changed the scope of their daily lives. They lived through it as they have embraced other challenges in the past: by successfully adapting. It has always been part of their nature to embrace any challenges put before them by dealing with them the best they know how and going on with the task of surviving. (Gagnon 59-60)

For a discussion of the emergence of new Inuit art in the face of colonial roadblocks, see:

Graff, Julie. “Qanuqtuurungnarniq: Facing Cultural Loss in Inuit Arts.” ICOFOM Study Series, no. 50–2, 30 May 2023, pp. 33–43, https://doi.org/10.4000/iss.4436.

Abstract

This paper examines the perspectives of Inuit intellectuals and artists on cultural loss, and the subsequent strategies of preservation and revitalization. Far from being passively suffered, the impact of colonial policies on the cultural continuity of Inuit societies has motivated the emergence of strategies for cultural preservation, transmission, and revitalization centered on individual and collective creativity. The first part of the article focuses on the enunciation and denunciation of cultural erosion by Inuit artists and intellectuals. The second part of the article focuses on some of the strategies established in response to these feelings of loss.

---

Alootook Ipellie entry by Lara Estlin. July 2020. Lara completed her BA in the Department of English at SFU and then went on to complete her MA (English) at UBC. She worked as a research assistant for The People and the Text from 2018 to 2020.

Additional Resources collected by Eli Davidovici in April 2024. Eli completed his M.Mus. at McGill University in June 2024.

Entry edits by Margery Fee, April 2024. Margery Fee is Professor Emerita at UBC in the Department of English.

Please contact Deanna Reder at dhr@sfu.ca with any comments or corrections.

Endnotes:

[1] For more on the history of Canada’s settlement initiatives in the North and how they impacted the lives of Ipellie and his family, see McMahon-Coleman, Indigenous Diasporic Literature: Representations of the Shaman in the Works of Sam Watson and Alootook Ipellie, PhD dissertation, University of Wollongong, 2009, pp. 98-100.

[2] For more on how the Canadian government’s health and relocation policies affected Ipellie’s generation and created an Inuit diaspora, see chapter one of McMahon’s dissertation, “A Place of Terror and Limitless Possibilities: Arctic ‘Exploration’ and Inuit History,” (71-97) and chapter two, “Arctic Dreams and Urban Reality: The Personal History and Influences of Alootook Ipellie (98-110, 116).

[3] For more on the influence of alcohol on Inuit communities and Ipellie’s family, see Ipellie’s comments in “Those Were the Days VII,” Inuit Monthly, vol.3, no. 9, 1974, p. 84, and “Those Were the Days XII,” Inuit Today, vol. 4, no. 7, 1975, pp. 67-69. See also McMahon-Coleman’s Indigenous Diasporic Literature, pp. 101-102, 110.

[4] Taking in and adopting children from the community as one’s own, if their immediate family or caregivers died or if they weren’t receiving proper care, was a common practice in Inuit culture that Ipellie’s grandparents continued (McMahon Indigenous Diasporic Literature 104; Bennett and Susan Rowley 40-42).

[5] Ipellie’s grandfather’s name has been anglicized in some records as Eenutsia and in others as Ennutsiak.

[6] For more on Ipellie’s childhood, his relationship to his mother, and the ways in which his uncle and grandparents influenced his early life and instilled a sense of Inuit values and cultural identity in him, see Ipellie’s reflection on the matter in “Those Were the Days VII,” pp. 82-84. See also Kennedy’s interview with Ipellie in “Alootook Ipellie: The Voice of an Inuk Artist,” pp. 157-159.

[7] Education is a theme Ipellie continually returns to throughout many of his publications. For a reflection on the schooling he received, see his introduction to Arctic Dreams, pp. vi-vii. For more on his views regarding Canada’s education system and its impact on Inuit youth, see “Those Were the Days IX,” Inuit Today, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 70-73 and “Those Were the Days XIV,” Inuit Today, vol. 4, no. 10, 1975, pp. 46-49.

[8] For a more in-depth reflection on the ideas and issues expressed in Ipellie’s political cartoons, as well as how he balanced serious subjects with humour and wit, see Kennedy’s interview, “Alootook Ipellie,” pp. 160-161.

[9] For a critical analysis of the stories in Arctic Dreams, see McMahon-Coleman “Dreaming an Identity Between Two Cultures: The Works of Alootook Ipellie,” pp. 108-125. For an analysis of Arctic Dreams in conversation with other texts produced by Ipellie, see Kennedy’s “Southern Exposure: Belated Recognition of a Significant Inuk Writer-Artist” (1995) and “Border under Siege: An Author’s Attempt to Reconcile two Cultures” (2002).

[10] In fact, the supposedly “clashing” components of Ipellie’s artwork were, one scholar presumes, likely the reason behind Theytus Books’ initial rejection of Ipellie’s Arctic Dreams and Nightmares in 1990 (McMahon-Coleman Indigenous Diasporic Literature 95). For more on how Ipellie’s work does or does not fit within traditional genres and styles of Inuit art, see McMahon-Coleman, Indigenous Diasporic Literature, pp. 13, 110-111, 117. See also Ipellie’s reflection on art critics’ inability to categorize his work in his introduction to Arctic Dreams, especially pp. xvi-xvii.

(Photo by John MacDonald)