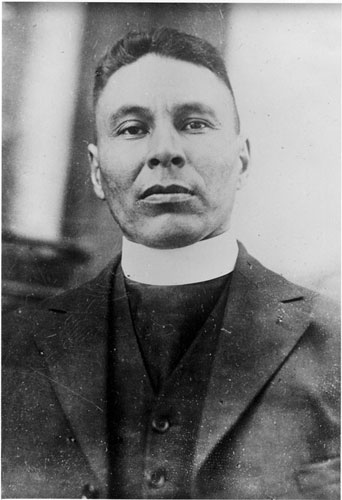

Edward Ahenakew (11 June 1885 - 12 July 1961)

Edward Ahenakew was born in 1885, a year of such tremendous upheaval for his people that it is referred to in Cree as ê-kî-mâyahkâmikahk, “where it went wrong” (McLeod 84). Born into a Christian family and, as part of the second generation of Plains Cree who grew up on the reserve in the aftermath of the North-West Resistance (sometimes called the second Riel Rebellion), Ahenakew would become a well-known speaker, activist, writer, and devoted Christian. Described as a quiet, sincere and deeply respectful man who nonetheless had a powerful voice and commanding presence, Ahenakew also had a keen sense of humour and was apt at “fully exploiting the humorous possibilities of the Cree language” (Stan Cuthand xii, xix; Hodgson vii). Today, Ahenakew is recognized as a spokesperson for his people and has even been compared to a Cree Martin Luther King (Doug Cuthand 22), as a political and spiritual person who, despite living most of his life in near-poverty, worked tirelessly within the church to improve the conditions of the Plains Cree.

Born at Ahtahkakoop’s Reserve[i] in Sandy Lake, Ahenakew recalls spending his early years growing up in a log house “thatched with mud and hay,” with a beautiful lake nearby in a community surrounded by a “bold and hilly” landscape covered with spruce trees (“Genealogical Sketch of my Family” 1). Both his father, Baptiste Ahenakew, and his mother, Ellen Ahenakew, cared for him as best they could throughout his early childhood—a period during which he was a frail toddler who developed ailments that caused him to become quite weak. At one point he was unable to eat for nearly a dozen days. In a passage that typically combines the lighthearted and the serious, he credits for his recovery both a strawberry his cousin gave him on the eleventh day of his illness as well as his mother who, inspired by the story of Samuel, prayed to God to save her son’s life in exchange for his future service in the ministry.[ii]

When Ahenakew turned eleven, his parents decided to follow through with their promise and took him to a residential school in Prince Albert where, Ahenakew notes, a basic education and religious training were offered but living conditions were poor (“Genealogical Sketch” 3). Both a good student and athlete, Ahenakew went on to attend Wycliffe College (University of Toronto) and later transferred to Emmanuel College in Saskatoon—a boarding school that was established in the 1880s to train future teachers and pastors for the Church of England—where he obtained a Licentiate of Theology in 1910 and was later appointed deacon.[iii] In 1912 he was ordained an Anglican priest.[iv]

Many of his early years as a minister were spent travelling from one reserve to another in the Saskatchewan diocese and later to church synods across Canada. While he was working in Onion Lake, Ahenakew bore witness to the devastating effects of the Spanish influenza of 1918. Spread by soldiers returning from Europe after World War I, the epidemic hit Indigenous communities particularly hard. Moved by the mass funerals on the reserves, when the churches were piled high with bodies (Ahenakew qtd. in Stan Cuthand xii), Ahenakew began to study medicine at the University of Alberta. However, his hopes of becoming a doctor were dashed when his physical and mental health deteriorated, likely as a result of stress and malnutrition, and he reluctantly decided not to complete his final two years.[v] Instead, he returned to what he considered his calling—church work—which he continued for the rest of his life.

Ahenakew’s life and work were not, however, confined to the Anglican diocese. Throughout the late 1910s and early 1920s, he had also developed political and literary aspirations: he contributed to a period of developing political consciousness among the Cree and helped give rise to a productive period for Indigenous literary development.

Ahenakew’s political activism involved speaking to a variety of audiences about topics ranging from educational reform to Cree sovereignty and self-determination. He participated in, organized, and led annual meetings for the League of Indians of Canada, an organization formed shortly after World War I in an effort to unite Indigenous people across Canada under one political organization, and in 1932 he became the League’s vice president. Around this time, Ahenakew developed an interest in educational reform and improvement, and pressured parliament to increase funding for children’s education on the reserves. A critic of the residential school system, he argued that it was “well meant” but ultimately unwise, “unnatural,” completely “contrary to our whole way of life,” and that it robbed Indigenous children of “all the initiative there may be in an Indian” (Ahenakew qtd. in “Student Accounts,” 180-181). Instead, he argued for well-funded reserve schools so that children could remain with their families (Ahenakew “Little Pine” 57).[vi] In 1933, however, after a trip to Ottawa in order to advocate on behalf of the League, he was forced to step down from his position when the Indian Department pressured the bishop to tell him to “attend to his duties as a churchman and not meddle in the affairs of the state” (Stan Cuthand xviii). As a result, he resigned from the League. Although Ahenakew was a cautious man who outwardly had great respect for and deference to authority, he often privately expressed his personal dissatisfaction and growing pessimism with the government’s manipulative handling of Indian Affairs.[vii]

The precariousness of his position as a Cree Christian working within colonial political and religious institutions is also evident in his writing, much of which is semi-autobiographical.[viii] In fact, Ahenakew produced a considerable body of work, but little has been published, because he often positioned himself outside those roles sanctioned by the church and the state.[ix] As early as 1903 he had founded a newsletter written in Cree syllabics, a precursor to what would become his Cree Monthly Guide (in Cree: Nehiyaw Okiskinotahikowin), produced with the help of the Missionary Society of the Church in Canada (MSCC) from 1925 until his death in 1961.[x] Around 1915, he became interested in the Northwest Rebellion and wrote a handful of reflections, as well as poems, which detailed the Frog Lake Massacre and took issue with the ways in which it had unjustly tainted the reputation of Indigenous peoples in the Northwest.[xi] Around 1918, he wrote an as-yet-unpublished novel with the title, Black Hawk, which outlined the changing agricultural and economic landscape of the early twentieth century. They revealed how the manipulative treaty making practices of the past and the policies of the present constricted Indigenous people’s freedom, causing famine and uprooting their traditional ways of life, and detailed the rules and restrictions imposed on Indigenous communities by the government—restrictions that regulated their activities on reserves and were enforced by autocratic Indian Agents with little concern for the welfare of the people they were charged with overseeing.[xii]

In the early 1920s, his best-known work to date, Old Keyam, was submitted to Ryerson Press, and although it was not selected for publication, Ahenakew remained hopeful that it eventually would be.[xiii] It consisted primarily of a collection of stories and reflections told in the form of a monologue by a poor, genial man modeled on the icon of the “old man” who stands, like his people, “bewildered in the maze of things, not knowing exactly what to do, and hiding their keen sense of defeat under the assumed demeanour of indifference” (Ahenakew 51). Ahenakew likely created his protagonist in order “to get around the church’s censure of his political activities and its attempt to strangle his political voice” (Miller 254). Nonetheless, Old Keyam could not find a publisher. Decades later, around 1948, the American Philosophical Society and the Bureau of American Ethnology at the Smithsonian expressed interest in his text; however, it wasn’t until after his passing that the manuscript was given to a close family friend, Ruth M. Buck, who edited and published a shortened version of Old Keyam as a section (“Old Keyam”) in Voices of the Plains Cree (1973).[xiv] She filled the rest of the book with some unpublished stories that he’d collected from Chief Thunderchild (also known as Kapitikow)[xv] in the early 1920s. Although many details were cut from Chief Thunderchild’s original stories and much beauty lost for the sake of brevity (Stan Cuthand xiv), Ahenakew’s efforts to collect and record Cree history and oral literature attest to his commitment to preserve Cree culture. Some of the stories he’d collected were published in well-known journals, such as those in “Cree Trickster Tales” (1929), which appeared in the Journal of American Folklore and in Saskatchewan Harvest, a Golden Jubilee selection of song and story, edited by Carlyle King, and published by McClelland & Stewart in 1955.

Ahenakew’s contributions extend beyond Cree literature, however, to Cree language, history, and ethnology. In the 1930s, he worked with Archdeacon Richard Faries on the revision of E.A. Watkins’ 26,000-word Cree-English Dictionary of the Cree Language (1865 [1938]), which some consider his most important accomplishment (Stan Cuthand xix).

He also wrote a piece that was donated to the Boas Collection[xvi] in 1948, titled “Genealogical Sketch of My Family,” in which he offers a short autobiography, traces his family’s lineage and recounts vivid anecdotes about his relatives, community members, and ancestors, bringing their stories and personalities to life.[xvii]

In 1951 he revisited his interest in the Northwest Rebellion and penned an article in The Western Producer about the Frog Lake Massacre in which he framed the rebellion as a result of Indigenous peoples’ frustration and loss of freedom, and contested mainstream accounts that silenced Indigenous voices and cast them as a “dumb nation” (3) in order to preserve racialized and romanticized narratives of Indigenous people in Canadian history.

In 1947, thanks to his relentless work as a teacher, preacher, and speaker, Ahenakew was granted the honorary degree of Doctor of Divinity from Emmanuel College. He continued working well past the age of his retirement. In 1961, as he was traveling by train from Emma Lake, where he’d been teaching at the Lay Readers School, he suffered a stroke and passed away at a local hospital in Canora, Saskatchewan, on July 12th at the age of 76.

Posthumously celebrated chiefly for his preservation of and contributions to Cree literature, some have commented on the irony that Ahenakew dedicated his life to working for the church (Stan Cuthand xix)—a decidedly Western institution intent on eradicating the very traditions he managed to preserve. Indeed, to some, it may appear that Ahenakew’s life, politics, and texts are permeated with contradictions: he was both Christian and Cree; both a cleric and a Status Indian; both a defender and a critic of Cree cultural practices. These ostensible oppositions, however, need not be framed as irreconcilable binaries or, for that matter, as ironic lapses in his life or in his identity. As Cree-Metis scholar Deanna Reder has pointed out, the texts Ahenakew has left behind are rich with allusions to Cree perspectives and philosophy, where oppositions are not necessarily framed as exclusive binaries but can co-exist and be held together at the same time.[xviii] Although it may appear that Ahenakew dedicated himself to the church and to the spread of Western values, from order and propriety to religion and ideology, it was ultimately his Cree identity and upbringing that allowed him to do the work that he did, to exist in an unstable and rapidly changing era and yet maintain an identity as an activist and writer who was respected by his colleagues within the Anglican Church as well as the Cree communities he served.

Selected Readings

Ahenakew, Edward. Black Hawk. [not published]

---. “Cree Trickster Tales.” The Journal of American Folklore, vol. 42, no. 166, 1929, pp. 309-353.

---. “Genealogical Sketch of My Family.” Boas Linguistics Collection of the American Philosophical Society, Item 4188, 27 April 1948.

---. “The Story of the Ahenakews,” edited by Ruth M. Buck, Saskatchewan History, vol. 17, no. 1, 1964, pp. 12-23.

---. “Tanning Hides,” edited by Ruth M. Buck, The Beaver: Magazine of the North, Summer 1972, pp. 46-48.

---. Voices of the Plains Cree, edited by Ruth M. Buck, Canadian Plains Research Center, 1995.

Works Cited

Ahenakew, Edward. “Little Pine: An Indian Day School,” edited by Ruth Matheson Buck, Saskatchewan History, vol. 18, no. 2, 1965, pp. 55-62.

---. Voices of the Plains Cree, edited by Ruth M. Buck, Canadian Plains Research Center, 1995.

---. “Sixty-five Years Ago.” in The Western Producer Magazine, Jan 11, 1951, clipping in Collection R1454, Articles, Ahenakew, Edward, 1951, No I. 1a, Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan.

Cuthand, Doug. “Canon Edward Ahenakew.” Askiwina, Coteau Books, 2007, pp. 20-22.

Cuthand, Stan. “Introduction to the 1995 Edition.” Voices of the Plains Cree, edited by Ruth M. Buck, Canadian Plains Research Center, 1995, pp. ix-xxii.

Edwards, Brendan Frederick R.. “Edward Ahenakew: aspiring Plains Cree novelist and writer, respected clergyman, and amateur anthropologist.” A War of Wor(l)ds: Aboriginal Writing in Canada During the ‘Dark Days’ of the Early Twentieth Century, U of Saskatchewan, PhD dissertation, 2008, pp. 132-161. https://harvest.usask.ca/bitstream/handle/10388/etd-08192008-104306/WarofWorldsPhDEdwardsFinal.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 17 May 2020.

Hodgson, Christine Wilna. “Foreword.” Voices of the Plains Cree, edited by Ruth M. Buck, Canadian Plains Research Center, 1995, pp. vii-viii.

Knight. Natalie. Dispossessed Indigeneity: Literary Excavations of Internalized Colonialism. Simon Fraser U, PhD dissertation, 2018, pp. 27-68. http://summit.sfu.ca/item/18523. Accessed 6 May 2020.

McLeod, Neal. “Rethinking Treaty Six in the Spirit of Mistahi Maskwa (Big Bear).” The Canadian Journal of Native Studies, vol. 19, no.1, 1999, pp. 69-89.

Miller, David. “Edward Ahenakew’s Tutelage by Paul Wallace: Reluctant Scholarship, Inadvertent Preservation.” Gathering Place: Aboriginal and Fur Trade Histories, edited by Carolyn Podruchny and Laura Peers, UBC Press, 2010, pp. 249-73.

Payton, W.F. Project Canterbury: An Historical Sketch of the Diocese of Saskatchewan of the Anglican Church of Canada. The Anglican Diocese of Saskatchewan, 1974. http://anglicanhistory.org/canada/sk/payton1974/21.html. Accessed 6 May 2020.

Reder, Deanna. Autobiography as Indigenous Intellectual Tradition: Cree and Métis âcimisowina, Wilfrid Laurier UP, 2022.

---. “Understanding Cree Protocol in the Shifting Passages of ‘Old Keyam.’” Studies in Canadian Literature, vol. 31, no.1, 2006, pp. 50-64.

“Student Accounts of Residential School Life: 1867-1939.” Canada’s Residential Schools: The History, Part 1: Origins to 1939: The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, vol. 1, published for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, McGill-Queen’s UP, 2015, pp. 169-196.

---

Edward Ahenakew entry by Lara Estlin, July 2020. Lara completed her BA in the Department of English at SFU and then went on to complete her MA (English) at UBC. She worked as a research assistant for The People and the Text from 2018 to 2020.

Updated by Eli Davidovici in April 2024. Eli is completing his M.Mus. at McGill University.

Entry edits by Margery Fee, April 2024. Margery Fee is Professor Emerita at UBC in the Department of English.

Please contact Deanna Reder at dhr@sfu.ca regarding any comments or corrections at dhr@sfu.ca.

Endnotes

[i] Now Ahtahkakoop Cree Nation. The nation is named after Ahenakew’s granduncle, Chief Ah-tah-ka-koop (Star Blanket) who signed Treaty Six in 1876.

[ii] In the Old Testament, Samuel’s mother prays to God for a child and in exchange vows to “give him to the Lord for all the days of his life” (1 Samuel 1.11); upon being weaned, Samuel is indeed delivered into the ministry (1 Samuel 2.11) much like Ahenakew, whose parents sent him to residential school to serve God in return for sparing his life.

[iii] Emmanuel College is now the University of Saskatchewan. Emmanuel College was founded at Prince Albert in 1879 and was established and incorporated by Act of the Dominion Parliaments as "The University of Saskatchewan" in 1883. Emmanuel College moved to Saskatoon in 1909 when the provincial university was established. While retaining its university status, it relinquished its title in favour of the new university. St. Chad's College was established in Regina in 1907, and remained there until 1964, when it was amalgamated with Emmanuel College to form the College of Emmanuel & St. Chad. The College of Emmanuel & St. Chad is now affiliated with the University of Saskatchewan. For more information see: https://emmanuelstchad.ca/about/.

[iv] For a more detailed history of Ahenakew’s theological studies and schooling as well as his work as an Anglican minister, see Payton pp. 102-104.

[v] For more on the compounding effects of malnutrition, anxiety, alienation, and depression Ahenakew likely experienced as he worked towards his medical degree, see Stan Cuthand pp. xiii and Knight p. 38.

[vi] As Natalie Knight has pointed out, Ahenakew’s writings do not often discuss the residential schooling system in depth because his experiences may have been insurmountable for personal and fictional reflection (46-47); however, some of his views regarding residential school can be found in “Old Keyam,” pp. 89-92 as well as “Student Accounts of Residential School Life: 1867-1939,” pp. 180-181.

[vii] For more on Ahenakew’s private thoughts regarding the ways in which Canada’s government and religious institutions manipulated and oppressed Indigenous people like himself, see Stan Cuthand, pp. xvii-xiv.

[viii] For a discussion on how Ahenakew’s texts fall both into the category of autobiographical fiction and into âcimisowin, Cree autobiographical narratives, see Reder, chapters three and four, pp.59-93.

[ix] As Reder points out, “While it was acceptable for Ahenakew to act in roles that positioned the Cree as a vanishing people (as ethnographer to collect “Native American folklore” or as an informant to Cree linguists) or as a people in need of civilization (in his work as a missionary, spreading the gospel and Western standards of cleanliness and propriety)” it was not acceptable when Ahenakew stepped outside of roles sanctioned by the Church and State (Reder, 2006, 62). For more on Ahenakew’s literary production and publication history, see Edwards pp. 136-140 and 150-152; Miller, pp. 249-273; and Reder’s “Edward Ahenakew's Intertwined Unpublished Life-Inspired Stories: âniskwâcimopicikêwin in Old Keyam and Black Hawk,” pp. 79-93.

[x] Few remaining copies of the Cree Monthly Guide exist today. For more on the copies that have survived as well as what they looked like and featured, see Stan Cuthand’s “Introduction,” pp. xv-xvii. For a more detailed analysis of The Cree Monthly Guide’s history, see Edwards, pp. 140-145.

[xi] These poems and reflections were found in his journals but were never published. However, they likely served as inspiration for an article Ahenakew later penned for the Western Producer in 1951. They are currently housed in the Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan, and little scholarship exists on them; for a brief discussion of these papers and his views regarding the Frog Lake Massacre and the Northwest Rebellion, as well as an overview of the economic, political and social context that likely shaped and informed Ahenakew’s views growing up, see Knight pp. 27-68, especially pp. 40-43.

[xii] An excerpt of chapter six of Black Hawk has been published in an essay by Deanna Reder titled “Recuperating Indigenous Narratives: Making Legible the Documenting of Injustices” published in The Other Side of 150, edited by Linda M. Morra and Sarah Henzi in 2021, pp. 27-40.

[xiii] For more on the struggles Ahenakew faced in getting Old Keyam to a publisher, see Edwards, pp. 136-140 and pp. 150-152.

[xiv] Contemporary Ahenakew scholars use Old Keyam in italics to refer to the original manuscript Ahenakew had intended to publish as a book, and “Old Keyam” in quotation marks to refer to the version that was edited and published by Ruth M. Buck over a decade after his death as part of Voices of the Plains Cree. Originally published in 1973, Voices was reprinted in 1995. The 1995 edition is quoted here.

[xv] Chief Thunderchild (1849-1927) was also known as Peyasiw-Awasis and Kapitikow, Cree for “one who makes sound.” A follower of Big Bear’s resistance to Treaty Six in 1876 who later ended up signing the treaty, Thunderchild was well known for his stance on the treaty and for his persistent negotiations with the government. As both an impressive storyteller and a witness to the conflicts that characterized much of the late nineteenth century, he was perhaps as crucial to the preservation and continuance of Cree literature, culture, and history as Ahenakew was in recording in his stories.

[xvi] A Supplement to a Guide to Manuscripts Relating to The American Indian in the Library of The American Philosophical Society compiled by Daythal Kendall and published in 1982, lists item 4188 Ahenaakew, Edward with the title “Genealogical sketch of my family”, dates it as Apr. 27, 1948, and describes it as 85 pages long that “Includes autobiographical sketch; biographical sketch of parents and grandparents and some of their collateral relatives” Cf. No. 779.

[xvii] A similar piece, “The Story of the Ahenakews” (1964), was edited and published by Ruth M. Buck after Ahenakew’s death, and was informed by “Genealogical Sketch of My Family” (1948).

[xviii] For more on how Cree cultural values, such as kisteanemétowin (respect between people) which comes out of a complex epistemological system based on wâhkotowin, the interrelationship of all things, are deeply embedded in Cree philosophy—and how they can be read in Ahenakew’s life and texts—see chapter 3 of Reder 2022.