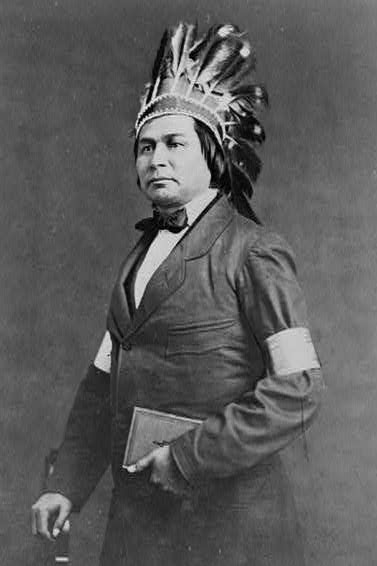

George Copway (1818-1869)

George Copway was a controversial author and activist who published the majority of his texts— including an autobiography, a travelogue, an ethnographic history, and a handful of political pamphlets—around the middle of the nineteenth century. The significant body of work he produced within a relatively short period of time and the brief popularity he achieved in both academic and popular spheres made him one of the earliest and most well-known authors to write about Indigenous concerns and perspectives in Canada.

Copway was born Kahgegagahbowh[1] (which translates as “Standing Firm” or “He who stands forever”) to Anishinaabe[2] parents near the mouth of the Trent River, around the Rice Lake area of what is now Ontario, Canada. In his autobiography, Copway describes his father (of the Crane tribe) as a medicine man and chief (12) and his mother (of the Eagle tribe) as an active, sensible woman and a good hunter (15). He also refers to his great-grandfather as an important warrior responsible for defeating the Hurons at Rice Lake, and credits him for establishing the community into which he was born (12). Copway reflects on his childhood in part by drawing on the conventional tropes of his time: he paints a largely Romantic picture of his younger self appreciating the woods (8) and glorying in “nature’s wide domain” (16); however, his repeated return to glimpses of his family’s poverty also reveals the hardships that the Copways faced as an Anishinaabe family attempting to maintain their traditional lifestyle on land was gradually being encroached upon, sold, and cleared by settler society.

In 1827, Copway’s parents converted to Christianity and three years later, shortly after his mother’s death, Copway did so as well, at age twelve. In the period that followed, he became increasingly interested in the tenets and teachings of Methodism, a denomination of Protestant Christianity that flourished between 1812 and 1850 in Upper Canada.[3] Much more liberal than other Christian factions, Methodism in its early stages welcomed people of all social ranks and colour, and was popular among Indigenous communities around the Great Lakes during the early nineteenth century. In 1834, Copway embarked on a missionary expedition to Lake Superior with three other converts and, in return for his service, received a two-year education from the Ebenezer Manual Labor School in Jacksonville, Illinois. Upon his graduation in 1839, Copway travelled back to Rice Lake, but not without making a number of stops along the East Coast in cities including Chicago, Detroit, Syracuse, Albany, New York, and Boston, where he met and cultivated relationships with Methodists and Quakers, and held both formal and informal sermons.

In 1840, Copway married Elizabeth Howell, who had immigrated to Toronto with her family from England, and whom he had met through Methodist acquaintances Peter Jones (Kahkewaquonaby) and Captain Howell. Throughout the 1840s, the couple travelled to several missions where Copway taught new converts to pray, sing, read, and write—skills he considered essential to the development of political consciousness and Indigenous self-empowerment in a period where illiteracy enabled settler society to manipulate written documents in its favour.[4] In 1845, Copway was elected vice president of the Grand Council of Methodist Ojibwas of Upper Canada. However, he was soon accused of embezzlement only a few months after his appointment, jailed twice by the Indian Department, and expelled from the Canadian Conference of the Wesleyan Methodist Church. Although, as one scholar has shown, Copway did have a tendency to spend more money on good causes than what was allotted to him by the Church, the disciplinary measures taken against him were extreme, especially considering the fact that embezzlement was not uncommon at the time, even among white preachers.[5] Copway’s sudden expulsion and ostracism from the Methodist Church also coincides curiously with the institution’s increasing conservatism and disintegration into different factions. Debates over issues like slavery, race, and national interests—all of which ultimately boiled down to questions regarding who could be included in and hold positions within the institution—gradually undermined the Church’s former claims to multiculturalism.

In the second half of the 1840s, Copway turned away from working with the Church and decided to focus his career on being a lecturer, writer, and activist, a decision that effectively catapulted him into the public sphere, launched his literary career, and brought him in touch with North America’s social and political elite, including notable writers like Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, Francis Parkman, William Cullen Bryant, James Fenimore Cooper, Washington Irving, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Copway’s first major publication was his Life, History, and Travels of Kah-ge-ga-gah-bowh (1847), in which he offers an autobiographical account of his life and experiences, details the changing landscape of his homeland, recounts Ojibwe customs, traditions, and history, and critiques settler society’s exploitation of Indigenous people and territory. Copway’s Life was incredibly successful: it went through several editions within a year of its publication[6] and was expanded and republished in 1850 under the title Recollections of a Forest Life. Later that year, Copway represented the Christian Indians at the World Peace Conference in Germany, and caused a stir when he showed up across the European continent to deliver speeches dressed in traditional Ojibwe clothing. His travels throughout Canada, the United States, and Europe not only allowed him to promote his work and cultivate his popularity as a prominent public figure but also served as inspiration for later books including his travelogue, Running Sketches of Men and Places (1851). Throughout the 1850s, Copway continued to deliver talks and write short pieces for newspapers on both sides of the border. In political pamphlets such as Organization of a New Indian Territory, he advocated for the establishment of a separate, sovereign state for Indigenous nations, which he planned to call Kahgega (meaning “Ever-to-be”), on land northeast of the Missouri River,[7] and in 1851, he launched a short-lived newspaper called Copway’s American Indian. Copway also wrote an ethnographic tribal history titled Traditional History and Characteristic Sketches of the Ojibway Nation (1851) and was credited with an epic poem called Ojibway Conquest, which an Indian agent, by the name of Julius Taylor Clark, had allowed Copway to publish under his name in order to raise money for his proposed sovereign territory.

Although Copway’s public influence and many accomplishments were impressive, the end of his life—which has been labelled by scholars as tragic, chaotic, and episodic—has tended to overshadow his achievements. Between 1849 and 1850, three of Copway’s four children passed away, and by 1861 he had separated from his wife permanently. Meanwhile, on the literary stage, his critics began speculating that he was not the rightful author of what he had written and insinuated that his wife was likely responsible for his successful literary career;[8] a number of accusations were levelled against him that tarnished his reputation, even though borrowing from other published sources—a practice that would be called “plagiarism” today—was quite commonplace in his own time. With his popularity waning, Copway was likely struggling to make ends meet: from 1861-1864, he recruited volunteers for the Union army and, around the year 1867, he began advertising his services in newspapers as a medicine man and healer. Scholars have had difficulty tracking Copway’s whereabouts throughout the 1860s but most agree that by 1868 he had found his way to Lac-des-deux-Montagnes (Oka) in Montreal, Canada, where he lived among the Haudenosaunee and the Algonquin for half a year, announced his intention to convert to Roman Catholicism, and changed his name to Joseph-Antoine before passing away suddenly in January of 1869. Although critics tend to focus on the fragmentation and gradual disintegration of both his public and private sense of self—by emphasizing, for example, the questionable choices Copway made towards the end of his life and by underscoring the notoriety those choices garnered him—it is worth keeping in mind the achievements that Copway, as one of the earliest and most popular Indigenous writers in Canada, was able to accomplish in a relatively short timeframe and in a period where institutions, from the Methodist Church to the printing press, were permeated with prejudice. Copway himself was acutely aware of his politically precarious position as a literate and very vocal Indigenous activist in nineteenth century North America; while he acknowledges, in the preface to his autobiography, that “I am an Indian, and am well aware of the difficulties I have to encounter to win the favorable notice of the white man” (2) he also reminds us that his existence and public presence as an Indigenous activist, spokesperson, and author speak to how “[w]hat was once impossible—or rather thought to be—is,” in fact, “possible,” as his own experiences and his literary legacy testify (7).

Selected Readings:

Copway, George. Life, Letters, and Speeches. Edited by A. LaVonne Brown Ruoff and Donald B. Smith, U of Nebraska P, 1997.

———. Running Sketches of Men and Places in England, France, Germany, Belgium, and Scotland. J.C. Riker, 1851.

https://archive.org/details/runningsketches02copwgoog

———. The Traditional History and Characteristic Sketches of the Ojibway Nation. Edited by Shelly Hulan, Wilfrid Laurier UP, 2014.

Works Cited:

Copway, George. The Life, History, and Travels, of Kah-ge-ga-gah-bowh (George Copway), a young Indian chief of the Ojebwa nation, a convert to the Christian faith, and a missionary to his people for twelve years. Weed and Parsons, 1847. https://archive.org/details/lifehistoryandt00copwgoog

Konkle, Maureen. “Traditional History in Ojibwe Writing.” Writing Indian Nations: Native Intellectuals and the Politics of Historiography, 1827-1863. U of North Carolina P, 2004. pp. 151-205.

Morgan, Cecilia. “Kahgegagahbowh’s (George Copway’s) Transatlantic Performance: Running Sketches, 1850.” Cultural & Social History, vol. 9, no. 4, Dec. 2012, pp. 527-548.

Penner, Robert. “The Ojibwe Renaissance: Transnational Evangelicalism and the Making of an Algonquian Intelligentsia, 1812–1867.” American Review of Canadian Studies, vol. 45, no. 1, Mar. 2015, pp. 71-92.

Petrone, Penny. “George Copway.” The Oxford Companion to Canadian Literature, Edited by Eugene Benson and William Toye, 2nd ed., Oxford UP Canada, 1997. pp. 233-234.

Peyer, Bernd C. “George Copway, Canadian Ojibwa Methodist and Romantic Cosmopolite.” The Tutor’d Mind: Indian Missionary-Writers in Antebellum America, U of Massachusetts P, 1997. pp. 224-277.

Reder, Deanna. “George Copway’s Autobiography: Land Claims to Reclaim pimatiziwin.” Âcimisowin as Theoretical Practice: Autobiography as Intellectual Tradition in Canada. UBC, PhD dissertation. 2007. pp.158-176.

———. “Indigenous Autobiography in Canada: Uncovering Intellectual Traditions.” The Oxford Handbook of Canadian Literature. Edited by Cynthia Sugars, Oxford UP, 2016. pp. 170-190.

Rex, Cathy. “Survivance and Fluidity: George Copway’s The Life, History, and Travels of Kah-Ge-Ga-Gah-Bowh.” Studies in American Indian Literatures, vol. 18, no. 2, 2006, pp. 1-33.

Ruoff, A. LaVonne Brown. “The Literary and Methodist Contexts of George Copway’s Life, Letters and Speeches,” Edited by A. LaVonne Brown Ruoff and Donald B. Smith, U of Nebraska P, 1997. pp. 1-22.

Smith, Donald B. “Kahgegagahbowh: Canada’s First Literary Celebrity in the United States.” Life Letters and Speeches, Edited by A. LaVonne Brown Ruoff and Donald B. Smith, U of Nebraska P, 1997. pp. 23-60.

———. “Literary Celebrity: George Copway, or Kahgegagahbowh (1818-1869).” Mississauga Portraits: Ojibwe Voices from Nineteenth-Century Canada, U of Toronto P, 2013. pp. 164-211.

Walker, Cheryl. Indian Nation: Native American Literature and Nineteenth-Century Nationalisms, Duke UP, 1997.

Endnotes:

[1] Recently, some scholars have begun referring to Copway by his Anishinaabe name, Kahgegagahbowh. I am using “Copway” rather than Kahgegagahbowh, since this is the name he usually uses in his texts and legal documents and since, for the purposes of literary analysis, “Copway” refers more directly to the textual self he constructs in his autobiography and self-narrated texts.

[2] Copway most often refers to himself as Ojibwa/Ojibway/Ojibwe, but contemporary scholars and members of the Anishinaabe community prefer Anishinaabe, which I use here, unless quoting or paraphrasing Copway or other scholars.

[3] For more information on Methodism’s popularity among Christian Ojibwe communities, see Robert Penner’s article, “The Ojibwe Renaissance: Transnational Evangelicalism and the Making of an Algonquian Intelligentsia, 1812–1867.”

[4] For more on the triangular relationship between Christian conversion, literacy, and political consciousness, see Deanna Reder’s “George Copway’s Autobiography: Land Claims to Reclaim pimatiziwin,” pp. 168-169.

[5] Copway has been impugned both in his time and in our own for his poor financial management skills. Bernd C. Peyer, however, reminds us that, in the nineteenth century, monetary mismanagement was actually quite common among Indigenous preachers and Indian agents alike (242). In Donald B. Smith’s most recent work on Copway, “Literary Celebrity: George Copway, or Kahgegagahbowh (1818-1869),” Smith also qualifies Copway’s misdeeds by reminding us that Canadian authorities treated him with severity (at one point jailing him without actually laying charges), and that his overspending pales in contrast to the Indian Department’s decade-long mistreatment and mismanagement of First Nations monies (183). For a more detailed discussion of Copway’s financial management skills and his reasons for overspending, see Smith’s “Literary Celebrity,” pp.178-184.

[6] Scholars are divided on the number of editions Copway’s Life went through in its first year: six, according to Petrone (233); seven, according to Rex (1), Konkle (191), Walker (87) and Smith (“Kahgegagahbowh” 33).

[7] Copway envisioned “Kahgega” as an English-speaking Christian Anishinaabe territory run by a democratically elected Anglo-American governor and a Native American lieutenant governor. He proposed that it be separate but equal to other American states, and anticipated that it might one day be granted statehood in the American Union. Three governors were won over to his cause and, although his plan was rejected by the federal government in 1849, Copway continued campaigning for it well into the 1850s. For more on Copway’s proposed territory, see Smith’s “Literary Celebrity,” pp. 190-191.

[8] It is difficult to determine the extent to which editors, including Elizabeth Copway, influenced Copway’s writing (Petrone 234), but many scholars are quick to assume that editorial involvement either evinces Copway’s literary shortcomings and his need for assistance (Peyer 238-239; Smith “Kahgegagahbowh” 40) or detracts from Copway’s own authentic voice (Ruoff 19; Walker 85-87). Worth keeping in mind, however, is that no piece of writing ever has a single source or completely coherent authorial voice, that works are often collaborative, and that, as some scholars have recently shown, it was common (also among white writers) for spouses and close family friends to read, comment on, and suggest revisions for an author’s work before publication (Morgan 530-531; Rex 26-27).

---

George Copway entry by Lara Estlin, July 2020. Lara is a former Simon Fraser University student who completed her English Honours project on Indigenous authors William Apess (Pequot) and George Copway (Anishinaabe). After completing her BA at SFU, she then completed her MA in the Department of English at UBC. She worked as a research assistant for The People and the Text from 2018-2020.

Entry edits by Margery Fee, April 2024. Margery Fee is Professor Emerita at UBC in the Department of English.

Updated by Eli Davidovici in April 2024. Eli completed his M.Mus. at McGill University in June 2024.

Please contact Deanna Reder at dhr@sfu.ca with any comments or corrections.