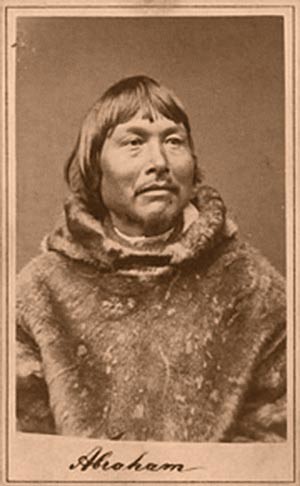

Abraham Ulrikab (1845-1881)

Abraham Ulrikab was an Inuk from Labrador who, with his wife, two daughters, a young relative, and another Inuit family, agreed to go to Europe to be part of an exotic traveling show, a so-called “human zoo”. Ulrikab, a devout Moravian Christian, spoke three languages and played violin, guitar and clarinet. He kept a travel diary during his voyage to Europe and also wrote letters to Brother Augustus Ferdinand Elsner, the Moravian missionary who was his teacher in Labrador. These are the only personal records of the short, tragic time he and the others spent as part of the ethnographic exhibition.

Abraham was born on January 29, 1845 in Hebron, to Paulus and Elizabeth, one of at least four other children. He was baptized on February 25, 1845. At this time the Inuit did not use surnames; it was customary for married people to take the first name of their spouse so Abraham Ulrikab meant Abraham, husband of Ulrike.[1]

In the late 1800s, Carl Hagenbeck, known as the creator of the modern zoo, began to exhibit human subjects in Germany. He found great success in ethnographic shows that included “primitive races” such as “Nubians,” “Laplanders” and “Eskimos.” Seeking to recruit more families, Hagenbeck hired a Norwegian, Johan Adrian Jacobsen, to travel to Greenland to find a group of Inuit to work for him. He had no luck there and ended up on the coast of Labrador at the small village of Hebron, where Moravian missionaries lived with the Inuit. The missionaries were very much against the idea of their Christian charges accompanying Jacobsen back to Europe, feeling it would expose them to “moral dangers” which had “proved very injurious to a company of natives of North Greenland similarly exhibited” three years before (Rivet 53). They would not allow Jacobsen to court the local Inuit, but he did manage to hire one, Abraham, to help him find non-Christian Inuit in Nachvak. Attracted by the opportunity to earn money to pay his debts, Ulrikab was convinced to go to Europe. He brought his wife Ulrike, 24 years old, and his daughters Sara, 3 years old, and Maria, 9 months. They were accompanied by a young man, Tobias, and a non-Christian family: Tigianniak, 45 years old, his wife Paingu, about 50, and their daughter Nuggasak, 15. [2] Jacobsen was aware that the group must be inoculated for smallpox to enter Germany but there was no doctor in Labrador. He planned to have it done as soon as they arrived in Europe.

On August 26, 1880, they set sail for Hamburg, Germany. According to Jacobsen’s diary the going was rough and the Inuit suffered from sea sickness. When they arrived on September 24 Jacobsen became very ill and neglected to obtain vaccinations for his charges. Instead, the Inuit party were put on display at Hagenbeck’s zoo immediately, performing daily with demonstrations of skills such as harpooning and kayaking. A few weeks later they traveled by train to Berlin to stay at the zoo there.

Ulrikab experienced culture shock and wrote about the constant unbearable noise in the cities. The crowds of people that came to see them were relentless, pushing up to them and even inside their dwellings. At one point he writes that he took up a whip and harpoon and “made [himself] terrible” to chase a crowd away (Lutz 41). The damp climate gave them all constant chills and runny noses. In one of his letters, he writes about how Tobias was beaten badly with a whip by Jacobsen for misbehaving and became very sick afterwards. He also writes of the bad food: too much bread and very little of what they were used to. There is only one high point in their travels, when they were visited by members of their church, eight Moravian brothers and sisters. That seems to be their only joy in the trip although Abraham wrote that Tobias delighted and cared for the children that had come to see them.

The Inuit were seen as a vanishing race. One Berlin newspaper describes the drastically declining population of their homeland: “One can almost predict the year when the people of the Labrador Eskimos will be entirely gone from earth” (Oct. 26, 1880, Abendausgabe, evening edition).

When the Inuit did get smallpox, it took them quickly. The first, Nuggasak, died in Paris on 14 December. Ulrikab wrote his last letter to Brother Elsner from Paris. “Terrianiak’s daughter, [she] stopped living very fast and suffered terribly. After [her] mother also died, greatly suffering as well” (Lutz 55). Paingu passed on 27 December and Sara four days after her. The remaining five were vaccinated on 1 January 1881, but it was far too late. They all died within the next few weeks. Ulrike was the last to pass, on 16 January 1881.

While their bodies were never returned to Labrador, some of their possessions, including Ulrikab’s diary, were sent back to Hebron. A missionary, Brother Kretschmer, translated the diary into German; the original, in Inuktitut, went missing. The translation was discovered in 1980, almost a century later, by J. Garth Taylor, who published an article about Ulrikab in Canadian Geographic in 1981. In 2005, Hartmut Lutz and Hilk Thode-Arora, with the help of students from the University of Greifswald, Germany, published The Diary of Abraham Ulrikab: Text and Content. This included Ulrikab's diary, as well as extracts from German newspaper articles and parts of Jacobsen’s journal, all translated from German into English.

In 2010, after reading The Diary of Abraham Ulrikab, France Rivet was inspired to try to discover more about the families. Rivet eventually discovered that the remains of Abraham, his wife Ulrike, his daughter Maria, Tobias, Tigianniak, and part of the skull of his wife Paingu are located in a French museum. Rivet also found that the skull of Abraham’s daughter Sara is part of a collection in Berlin. Rivet published her discoveries in a book, In the Footsteps of Abraham Ulrikab, 2014. As of yet, their remains have not been brought home.

Works Cited:

Lutz, Hartmut, and Abraham Ulrikab. The Diary of Abraham Ulrikab: Text and Context. U of Ottawa P, 2005.

Rivet, France. In the Footsteps of Abraham Ulrikab. Polar Horizons, 2014. https://polarhorizons.com/en/abraham-ulrikab.

Taylor, J. Garth. “An Eskimo Abroad, 1880: His Diary and Death” Canadian Geographic, vol. 101, no. 5, 1981, pp. 38-43.

Additional Resources:

For a discussion about: Ulrikab’s diary used as evidence that Inuit remains and significant artifacts are held in French and German museums, see:

Rivet, France. “Ethnographic Objects Associated with the Labrador Inuit Who Were Exhibited in Europe in 1880” Études Inuit Studies vol. 42, no.1-2, 2018, pp.137-159. https://doi.org/10.7202/1064499ar

Abstract

In the summer of 1880 eight Inuit from northern Labrador, consisting of members of two families, agreed to travel to Europe where, in exchange for payment, they were to exhibit themselves and their culture to audiences in large cities. Their recruiter, the Norwegian Johan Adrian Jacobsen, took advantage of his stay in Hebron and Nachvak Fjord to collect a series of grave artifacts, which he exhibited with the eight people. Tragically, because Jacobsen neglected to have the two families immunized before departing for Europe, all eight died of smallpox in less than four months after their arrival on European soil. In 2014, author France Rivet reveals in her book, In the Footsteps of Abraham Ulrikab, that French and German museum collections contain not only a set of grave artifacts assembled by Jacobsen but also the human remains of the members of the two families as well as some of the objects that belonged to them. This article is intended to be an update on the nature of the objects and how the European museums collected and acquired them.

For an ethical analysis of the human remains trade and machine learning, using Ulrikab’s case as an example of repatriation, see:

Huffer, D., Wood, C. and Graham, S. “What the Machine Saw: some questions on the ethics of computer vision and machine learning to investigate human remains trafficking,” Internet Archaeology, vol. 52, 2019: https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.52.5

Excerpt from Introduction:

Jacobsen neglected to have the eight travellers immunised when they arrived and they fell ill within weeks. Less than four months later, all had died of smallpox (Rivet 2014). With the help of [Ulrikab’s] diary, and that of Jacobsen, researchers have been able to locate the travellers’ mortal remains (Rivet 2014). After their deaths, the skeletons of Abraham, Ulrike, Maria, Tobiasm and Tiginaniak from Nakvak were mounted and kept by the Musée National d’Histoire Naturelle. Tioganniak’s wife Paingu and daughter Nuggasak died before reaching Paris, and part of Paingu’s skill is also in the Paris collection (Rivet 2014). Sara’s body was kept in a collection in Berlin (Rivet 2014). The translation of Ulrikab’s diary, and further research with European institutions and Nunatsiavut communities in Labrado, has meant the initiation of a repatriation process (Rivet 2015; 2016). Through the Inuit have not yet been returned home, the story and fate of Ulrikab, and his family and fellow travellers prompts one to ask: how many other Abraham’s are there out there?

Contrast Abraham Ulrikab's story - the result of patient historical research - against the story told by the human remains collecting community (we discuss in depth the texts of collectors' and dealers' posts in Huffer and Graham 2017). Examining the posts themselves and their associated comments and discussion, it seems that it is the adventure story that can be told about these remains that is part of the 'cachet' generating the monetary value exchanged. But the story is not one of lives lived, and they are not stories tied to named individuals. Instead, the focal point is the 'artistic expression', the 'beauty' of the thing. The exotic. The anonymity is part of the point, because it allows the collector to project their fantasies. A heroic collector tells this story of the transformation of human remains into commodities, and a constant search for the allegedly old, authentic, rare and macabre.

The contrast between the ‘actual’ story and the collector's ‘stock’ narrative is why we presented the tragic case of Abraham Ulrikab. It is to highlight the colonial violence at the heart of these collections of human remains, many of which have (one way or another) been released into the market, a violence that depends crucially on ways of looking, of consuming, of constructing, an exotic ‘other’. It is a literal dehumanising: a named individual becomes a mere thing. Ulrikab's story is not unique - others that spring to mind immediately include the way Sarah Baartman was put on display while living, and her body dissected and displayed after death by George Cuvier within the Musée de l'Homme in Paris; the story of White Fox, a Pawnee who died in Sweden and was eventually repatriated in 1996 (Jibréus 2014); and the thousands of skulls collected under the auspices of colonial governments in Africa (Tharoor 2016), which include such leaders of uprisings as Chief Songea Mbano (Gross 2018). This raises our crucial ethical question concerning using machine vision to study these materials and their contexts of collecting: are we not just replicating a neocolonial violence?

For an ethnographic study of European colonialism through the treatment of Inuit as exhibitions, see:

Křížová, Markéta. “Alone in the Country of Catholics: Labrador Inuit in Prague (1880)” Sciendo vol. 20, no. 2, 2020, pp. 20-45. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2478/eas-2021-0010

Abstract

The ethnographic shows of the end of the 19th century responded to an increased hunger for the exotic, especially among the bourgeois classes in Europe and North America, and to the establishment of both physical and cultural anthropology as scientific disciplines with a need for study material. At the same time they served as a manifestation of European superiority in the time of the last phase of colonialist thrust to other continents. “Scientific colonialism” reached also to regions without actual colonial or imperial ambitions, as the story of Labrado Inuit who visited Prague during their tour of Europe in November 1880 will prove. The reactions of local intellectuals and the general public to the performances of the “savages” will be examined in the context of the Czech and German nationalist competition and the atmosphere of colonial complicity. Thanks to the testimony of a member of the group, Abraham Ulrikab, supplemented by newspaper articles and other sources, it is possible to explore the miscommunications arising from the fact that the Inuit were members of the Moravian Church, profession allegiance to old Protestand tradition in the Czech Lands and cultivating a fragmented knowledge of Czech history and culture.

For analysis of Ulrikab’s diary and how it pertains to Whiteness as a conceptual construct see:

Cantor, Javier. “Carl Hagenbeck’s Human Exhibitions and Whiteness (1880-1881) in Europe” Artificios: Revista Colombiana de Estudiantes de Historia, vol. 23, 2023, pp. 42-57.

Abstract

In the nineteenth century, paying to witness live performances by individuals from foreign lands was a popular phenomenon in Europe. Paradoxically, few traces of these exhibitions exist today. However, they created a legacy by shaping public atitudes toward ethnic differences. In this study, I will analyze the diary of Abraham Ulrikab, a performer who left seemingly the only written source produced by one of the performers (not to say that foreign people co-created many of the archival remains of these shows). Through this analysis, I laid bare how whiteness was constructed through a series of cultural practices, that have largely remained unnamed but that nonetheless are part of a process of domination. The bodies conveyed meanings that were devised from an invisible position, a zero-point a marker, against which differences were measured. Consequently, these exhibited bodies became part of a long-standing phenomenon that originated in 17th century London and subsequently expanded outwards. The human body was targeted not only for being the most intimate space, but the signified through which dominance was asserted and reinforced.

Endnotes:

1. In Europe, Abraham and his daughters were given his father’s first name as a surname, so Abraham Paulus. Ulrike gained the last name Henocq. The non-Christian family were not given surnames.

2. Some documents suggest that Tobias may have been a nephew of Ulrike or Abraham. Others say he was just a young bachelor (Rivet 49).

---

Abraham Ulrikab entry by Kimberley John, September 2018. Kimberley is an alumnus of SFU, graduating with a Double Major in Health Sciences and Indigenous Studies. She worked as a research assistant for The People and the Text from 2016 to 2020.

Additional Resources collected by Eli Davidovici in April 2024. Eli is an alumnus of McGill University, graduating with an M.Mus. in Jazz Performance in Summer 2024.

Entry edits by Margery Fee, April 2024. Margery Fee is Professor Emerita at UBC in the Department of English.

Please contact Deanna Reder at dhr@sfu.ca regarding any comments or corrections at dhr@sfu.ca.